This is a David and Goliath story of the 16th century. "David" was Dutch rebel William de la Marck. "Goliath" was the mighty Philip II of Spain. Elizabeth I of England was the surprise catalyst of an uprising that sparked the Dutch War of Independence against Spain.

|

| Elizabeth I by William Sugar [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons |

In 1571 Elizabeth, at the age of thirty-eight, had reigned for thirteen years. She was far from secure on her throne. England had no standing army and an undersized navy, and Elizabeth feared that Philip of Spain, the most powerful monarch in Europe, was poised to invade. To strike at her, his army would sail from the Netherlands. There, less than a hundred miles off her shores, his troops had already subjugated the Dutch.

|

| Philip II |

Philip was lord of Spain, portions of the Italian peninsula, and the Low Countries (modern-day Belgium and the Netherlands) whose cities of Antwerp and Bruges were Europe's richest trading centres. He was also stupendously wealthy thanks to his vast New World possessions. The Spanish Main, a scythe-shaped slice of the globe, ran from Florida through Mexico and Central America to the north coast of South America, gateway to the riches of Peru.

Twice a year the Spanish treasure fleet, the flota, crossed the Atlantic to deliver hoards of New World gold, silver, and precious gems to Philip's treasury in Spain. Philip used this constant river of riches to finance his constant wars. Throughout Europe, Spain's armies were feared and triumphant.

Nowhere were they more feared than in the Netherlands. There, Philip's general, the Duke of Alba, had crushed Dutch resistance to Spanish rule. "The Iron Duke," as Alba was called, was governor of the Netherlands from 1567 and had set up a special court called the Council of Troubles under whose authority he executed thousands, including leading Dutch nobles. The people called it the Council of Blood. Here are Alba's own words: "It is better that a kingdom be laid waste and ruined through war for God and for the king, than maintained intact for the devil and his heretical horde."

|

| The Duke of Alba |

Religion, as always in the 16th century, was a fiery instrument of division. Philip of Spain was known as "the most Catholic prince in Christendom." Catholics considered Elizabeth of England a bastard, since they did not acknowledge her mother Anne Boleyn's marriage to her father Henry VIII, and a heretic, since Elizabeth's first act as queen had been to make the realm officially Protestant. That act had also made her the supreme head of the church in England, a concept that Catholics found grotesque: a woman as head of a church. In 1570 Pope Pious V excommunicated Elizabeth in a fierce decree, calling her a heretic and "the servant of crime." He released all her subjects from any allegiance to her, and excommunicated any who obeyed her orders. Scores of affluent Catholics left England with their families and settled in the Spanish-occupied Netherlands.

|

| Mary, Queen of Scots |

But the Dutch rebels had not given up, only gone to ground. They still considered Prince William of Orange their leader. He was keen for a second chance to win back his country for the Dutch. And Elizabeth of England was eager to secretly support him. That second chance came in the spring of 1572. This time the rebels would not come marching, as an army. They would come from the sea: a motley fleet called the Sea Beggars.

The origin of their name is intriguing. Before Alba's arrival in the Netherlands the governor was Philip's sister, Margaret. A delegation of over two hundred Dutch nobles appeared before her with a petition stating their grievances. She was alarmed at the appearance of so large a body, but one of her councillors exclaimed, "What, madam, is your highness afraid of these beggars?" The Dutch heard the insult, and after Margaret ignored their petition they declared they were ready to become beggars in their country's cause, and adopted the name "Beggars" with defiant pride. Scores of them took to the sea to harry Spanish shipping. Led by William de la Marck, they called themselves the Sea Beggars.

|

| William de la Marck |

For several years Elizabeth gave safe conduct to the Sea Beggars, allowing La Marck and his rebel mariners to make Dover and the creeks and bays along England's south coast their home as they continued their raids on Spanish shipping, which infuriated Philip. England was far weaker than mighty Spain, so Elizabeth was playing "a game of cat and mouse" with Philip, says historian Susan Ronald in her book The Pirate Queen; helping the Sea Beggars was "the only course open to her to show her defiance of Spain."

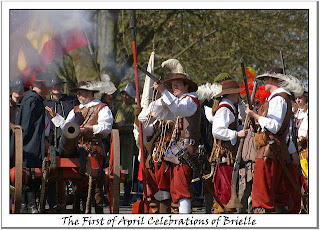

But as 1572 dawned Philips's fury grew dangerous. In March, Elizabeth ordered the expulsion of the Sea Beggars from her realm, an act that people assumed was to placate Philip. It turned out, however, that Elizabeth had struck a lethal blow at Spain: by expelling the Sea Beggars she had unleashed their latent power. For a month theses rebel privateers wandered the sea, homeless and hungry, until, on the first of April, they made a desperate attack on the Dutch port city of Brielle, which had been left unattended by the Spanish garrison. They astounded everyone, even themselves, by capturing the city.

|

| The Capture of Brielle |

Their victory provided the Dutch opposition's first foothold on land and launched a revolution: the Dutch War of Independence. The capture of Brielle gave heart to other Dutch cities suffering under Spain's harsh rule, and when the Sea Beggars pushed on inland they rejoiced to see town after town open their gates to them. The exiled Prince of Orange now sent troops to support them. But Spain ferociously struck back. Taking the rebel-held cities of Mechelen and Zutphen, the Duke of Alba's troops massacred the inhabitants; in Mechelen the atrocities went on for four days. The town of Haarlem bravely resisted during a long siege, but finally surrendered. Alba's troops methodically cut the throats of the entire garrison, some two thousand men, in cold blood.

By 1585 Elizabeth could no longer tolerate Spain's tyranny in the Netherlands, and she sent an army under the Earl of Leicester to support the Dutch revolution. Nevertheless, it took six decades more until the people of the Netherlands won their freedom, in 1648.

To this day, on the First of April every year, the Dutch people still exuberantly celebrate the Sea Beggars' capture of Brielle.

This Editor's Choice was first published on November 26, 2013.

~~~~~~~~~~

Barbara Kyle is the author of seven acclaimed historical novels – the Thornleigh Saga series – all published internationally, and of contemporary thrillers, three under pen-name Stephen Kyle, including Beyond Recall, a Literary Guild Selection. Her latest novel is The Traitor's Daughter. Over 500,000 copies of her books have been sold in seven countries. Barbara has taught writers at the University of Toronto School of Continuing Studies and is a popular guest presenter at writers' conferences. Before becoming an author Barbara enjoyed a twenty-year acting career in television, film, and stage productions in Canada and the U.S.

Barbara’s workshops, master classes, and manuscript evaluations have launched many writers to published success. She recently released a non-fiction writing resource, Page-Turner: Your Path to Writing a Novel That Publishers Want and Readers Buy. Barbara welcomes you to her website: www.BarbaraKyle.com.

The Sea Beggars feature in Barbara Kyle's novel The Queen's Exiles.

Barbara Kyle's six-book Thornleigh Saga follows an English middle-class family's rise through three tumultuous Tudor reigns.

"Riveting...adventurous...superb!" Historical Novel Society, "Editor's Choice."

"Kyle knows what historical fiction readers crave." RT Book Reviews

"A beautifully written and compelling novel. Again, Barbara Kyle reigns!” - New York Times bestselling author Karen Harper

Can't wait to read this novel. I found the sea beggars fascinating. Great post.

ReplyDeleteWhat a terrific chapter in history! Love the story!

ReplyDeleteI think the article should have mentioned that the Sea Beggars rounded up 19 Catholic priests and friars and hanged them after they had captured Brielle. Their bodies were mutilated during their executions and after, before they were dumped in a ditch on July 9, 1572. Also, five Franciscan friars were hung in Alkmaar on June 24, 1572; 12 Carthusians were attacked and murdered in the chapel of the Charterhouse of Our Lady of Bethlehem in Roermond, Holland, on July 30, 1572, by the soldiers of William the Silent; and the last prior of St. Agatha’s monastery in Leiden, Cornelius Musius, was arrested, tortured and finally executed by van der Marck on William the Silent’s orders on Dec. 10, 1572.The atrocities were not all on side. Some mention of these events would add balance and context to the article. Thank you.

ReplyDelete